https://www.splcenter.org/resources/reports/tensions-mounting-between-blacks-and-latinos-nationwide/

Around the country, evidence of a growing divide between blacks and Hispanics is mounting. It's a split few want to discuss.

One after another, the reports have rolled in. From Florida to California, Nevada to New Jersey, even as far away as the state of Washington, the news is getting harder to ignore: There’s trouble brewing between blacks and browns.

At Hug High School in Reno, Nev., an emergency task force began work last October after a series of fights between black and Hispanic students that interim Schools Superintendent Paul Dugan said reflected “definite racial tensions.” In Monroe, Wash., similar tensions shot up after a Mexican flag was torn down and thrown into a bathroom and several off-campus fights broke out. In Chicago, seven students were arrested after an interracial brawl in January left teachers and security guards injured and parents complaining of mounting racial strife.

But it was in schools in California, where so many of the nation’s trends first take shape, that this disturbing conflict was most obvious.

On Nov. 8, hundreds of black and Latino students got into two separate battles in the streets around Wilmer Amina Carter High School in Rialto. Two days later, another interracial fight broke out on campus, and four days after that a huge battle erupted in the lunchroom, leaving 57 of the hundreds of students involved injured. At around the same time, more than 20 police officers broke up a series of street fights between black and Latino students outside Fremont High School in Oakland that involved as many as 150 participants and bystanders. In San Jacinto, a riot at San Jacinto High School between black and Hispanic students resulted in three arrests, six suspensions and the lockdown of 1,700 students. Some 500 students were involved in the fight, and police reported some arriving parents added fuel to the fire by shouting racial slurs and urging their children to keep up the battle. Similar racial conflicts hit Crenshaw, Manual Arts and Jordan high schools in Los Angeles.

The Presumed Alliance

Traditionally, black and brown activists have seen themselves in a natural alliance in a country historically dominated by whites — an alliance of mostly poorer, darker-skinned minorities whose struggles are not dissimilar. But like the civil-rights-era alliance between blacks and Jews, the black/brown coalition has grown more and more strained. Many blacks resent what is seen as Hispanics leapfrogging them up the socioeconomic ladder, and some complain of the skin-color prejudices that are particularly strong in some Hispanic countries, notably Mexico. Just this May, the Rev. Al Sharpton bitterly demanded that Vicente Fox apologize after the Mexican president made what some blacks interpreted as a racist comment. Similarly, many Hispanics say they are treated in racist ways by blacks, some of whom have apparently singled out undocumented immigrants for robbery and worse.

The conflict is growing, as mainly Hispanic immigrants, legal and illegal, pour into neighborhoods that were in many cases previously dominated by blacks.

Many blacks say Hispanics generally will not hire blacks in their businesses, even though many cater to black customers. Many Hispanics say they are being targeted for robbery by blacks who pick on undocumented workers, a group far less likely to report crimes to police. Both groups worry about the implications of blacks’ 2002 displacement as the largest minority in America for the first time in history.

Nicolás Vaca, author of The Presumed Alliance: The Unspoken Conflict Between Latinos and Blacks and What it Means for America, said black radio talk show hosts have been hot to discuss his 2004 book. “Most thought that it was time that someone spoke about the elephant in the room,” Vaca told the Intelligence Report.

The elephant reappeared in the halls of Jefferson High School in South Los Angeles this April 14. A minor spat exploded into a lunchtime melée involving about 50 Latino and 50 black students. Four days later, police were sent in for a second time, this time to quell a battle involving some 200 students. Two students were arrested, four detained, and six hurt in minor ways. One broke a hip. Officials changed school schedules to keep the factions more separated. Metal detectors were installed. A Nation of Islam official offered protection to black students. Mayoral candidate Antonio Villaraigosa even addressed a forum called to discuss the strife, begging parents to “model for these young people black and brown unity.”

It didn’t happen. Less than a week later, a rumor that a violent Hispanic gang would be exacting retribution from black students the next day coursed through the school district. In the end, an astonishing 51,000 students stayed home.

Sizing up the Elephant

Tensions between blacks and Latinos are certainly not new. They have surfaced in major ways in Miami, where a relatively wealthy class of Cuban exiles has won far more political power than the city’s blacks, and Houston, where blacks and Latinos have often been on opposite sides of political races. (“There will be a Libertarian in the White House before there is a black-brown coalition in Houston,” Orlando Sanchez, who lost a close 2001 mayoral race to a black candidate, wryly told the Houston Chronicle this spring.) While the recent school conflicts have brought the issue to the fore, some writers have been trying to point it out for years.

In 1992, Jack Miles wrote a long essay about race in Los Angeles for the Atlantic Monthly magazine, “Blacks vs. Browns.” He was one of the first to describe competition for jobs, suggesting Hispanics were gaining the upper hand. “America’s older black poor and newer brown poor are on a collision course,” he wrote.

In 1995, Dallas Morning News columnist Richard Estrada, noting conflicts between blacks and Hispanics over hiring practices at a public hospital, warned of “contentiousness” between the two groups “that seems destined to grow.”

And three years after that, a book called Neighborhood Voices chronicled the feelings of black and Latino residents in Northeast Central Durham, N.C., where Hispanic immigration had transformed a formerly black part of the city. Many of the voices from both communities were remarkably bitter in their assessments.

But it was an article in the Charlotte Post, a newspaper in North Carolina that caters to black readers, that may have most starkly described the conflict. Published in March 2001, “When Worlds Collide: Blacks Have Reservations About Influx of Hispanic Immigrants” quoted a whole series of racist comments about Hispanics from blacks in the city. Writer Artellia Burch dispelled in no uncertain terms notions that blacks necessarily felt empathetic toward the struggles of Latinos.

E-mails and letters poured in. Fox News sent a camera crew. Post Publisher Gerald Johnson felt compelled to defend his reporter’s story, suggesting it showed that “racism is systemic” and blacks were “no different than anybody else.”

That wasn’t enough for many. BlackPressUSA.com removed the story from its Web site, saying it didn’t condone “stereotyping.” Raul Yzaguirre, the president of the National Council of La Raza, called on black leaders to denounce the story “in the strongest possible terms.” (Earlier, however, Yzaguirre had co-authored a calmer paper on black-Hispanic relations that concluded that “growing tension between the two communities … threatens the ability of blacks and Hispanics to develop strong, sustainable coalitions.”) Others also attacked the Charlotte Post piece.

None of this surprises Nicolás Vaca, author of The Presumed Alliance.

Early on in his book project, Vaca learned just how controversial the topic of black/brown relations was, and how incendiary. Merely discussing the project with two attorney friends ended a friendship as one stormed out of a restaurant.

“Why dig up dirt, ruffle feathers, destroy the illusion of unbroken unity between Blacks and Latinos, bleeding the colors of the Rainbow Coalition by giving the dreaded gringo the ammunition my former friend told me I was providing?” a dispirited Vaca wrote. “The simple answer is the ethnic landscape has changed.”

The Intelligence Report found the same reluctance to discuss the issue. Although the magazine contacted numerous black and brown thinkers and scholars to comment on the matter, virtually none would talk about it publicly.

Robbery, Racism and Reaction

Last summer, in the region around Plainfield, N.J., The New York Times reported that at least 17 Hispanic men were severely beaten by young black men and, in one case, killed. Some black leaders said they believed the attacks were about money, not bias, and there was no consensus among police as to the motive.

But the violence of the attacks seemed excessive, even when money was taken — a classic hallmark of a hate crime rather than simple robbery. “To hit someone with a baseball bat, you have to hate someone,” Michael Parenti, chief of the North Plainfield Police Department, told the newspaper. “To beat a guy for a few dollars never made a lot of sense to me. It looked to me like a bias incident.”

Unfortunately, available hate crime statistics are not much help in trying to gauge conflict between blacks and Hispanics. While national figures show around 100 black-on-Hispanic hate crimes for each of several recent years, there is virtually no doubt that that number vastly understates the violence. Moreover, the fbi has no similar statistics that would cast light on Hispanic violence against blacks. The most that can be said is that these types of hate crimes seem anecdotally to be rising.

Last September, a similar series of attacks broke out on the streets of Jacksonville, Fla. Again, it was hard to say definitively if robbery or hate was the main motivation for these crimes. What was clear was that in at least 28 different assaults, the perpetrators were black and the 68 victims Hispanic. Two people were murdered, while another eight people were shot but survived their wounds.

The Hispanic community, about 8% of Jacksonville’s population, was outraged. The local Spanish-language paper demanded an investigation. A press conference was held, and rumors of Hispanic retribution ran rampant.

A man named Nicolás is one of the victims.

Last fall, Nicolás and his father were robbed by a black man with a gun who walked into the family restaurant they were preparing to open. Nicolás says he’s not a racist, but the steady stream of young black men who walk through his parking lot on their way to and from local low-income housing has him concerned. And after the attack on him, once he got past his depression, he bought a handgun.

“There are good morenos [blacks], but there are also some that live off the government, welfare or disability, without working,” he says. “The vast majority of morenos are hard workers, but the rest of them want to live for free.”

Several hundred miles to the north, Shaneesha, a black student in Tanya Golash-Boza’s class on “Race and Ethnic Relations Between Blacks and Hispanics,” suffers from some of the same kinds of suspicions, as seen from the other side. She is studying in Chapel Hill at the University of North Carolina, a state Census figures show had a nearly 700% growth in its Hispanic population between 1990 and 2000.

“I’ve heard that Latinos don’t pay taxes, that they’re illegal, that they’re ignorant, that they’ll stab you,” Shaneesha says, although she adds that she was brought up to judge individuals on their merits alone. Studying at a university that in just the last few years has seen its support staff go from all-black to about half Latino, Shaneesha also worries about the possibility of economic competition from Hispanics. “As an African American, I can see how it could threaten me.”

In Detroit, politicians decided to do something about that.

African Town

“The issue of immigration is roiling within Black communities and has the potential to soon become a divisive issue of historic proportions,” says Claud Anderson, president of the black think tank Harvest Institute and one who does not shy away from expressing disdain for Latinos. In a January 2004 report, Anderson claimed that Hispanic immigrants come to this country for the “public service benefits available to them because of the Black Civil Rights Movement.”

Anderson says these Latinos invade black neighborhoods, and then use language and culture as barriers to economic integration. “Immigrants operate their businesses in Black communities, but they will not buy from black businesses and they rarely hire blacks as employees,” Anderson writes. For him, these Hispanics are deliberately trying to “push blacks off the upward ladder of success.”

Claud Anderson even has a conspiracy theory, claiming that the National Hispanic Party — a party no one else seems to have heard of — “declared a population war on Black Americans in the early 1970s at a mid-west meeting and crafted plans to numerically surpass and supplant Black Americans by the year 2000.”

No matter that Anderson sounds like a racist.

No matter that he openly advocates racial discrimination.

To many Detroit politicians, Anderson is the man with a plan. Last year, a majority of the city council commissioned a $112,000 economic development study from Anderson. His recommendation was that the city spend $30 million to develop something called “African Town” — an inner-city business enclave created for blacks that would keep them from spending money in immigrant businesses.

Anderson and others argued that the city had provided incentives to Mexicantown and Greektown, two neighborhoods marked by ethnic businesses and restaurants. Why shouldn’t it do the same for black businesses? After all, blacks made up 86% of Detroit’s population, and black business needed help. Anderson went further. Hispanics, he said in the kind of comment that lit up many citizens of Detroit, “have surpassed Blacks now and made them third-class citizens.”

In July 2004, the City Council passed a resolution approving African Town and the $30 million in casino revenues that it planned to disburse as grants and low-interest loans to “historically depressed documented residents of Detroit who are members of the city’s majority under-served population” — blacks, in other words.

The blacks-only funding plan outraged many.

Detroit News columnist Nolan Finley wrote that the Harvest Institute report “mimics the language of the most fascist, right-wing anti-immigration groups, with headings like “A Majority Should Dominate and Act Like a Majority,” and segments that warn of the dangers of Hispanics gaining a political voice. It could have been read on the public squares of Berlin in 1934 or on the Capitol steps of Birmingham, Ala., in 1964.” L. Brooks Patterson, an elected official from a neighboring county, told a reporter that African Town was “one of the dumbest ideas I’ve ever heard about and frankly insulting. How would residents of Detroit feel if I were to propose a Honky Town in [my county]? I would be run out of office, and rightfully so.”

Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, who is African-American, vetoed African Town last fall. But the council overrode his veto, although it did ultimately strike the requirement that all African Town subsidies be limited to black applicants.

Unity, Politics and Progress

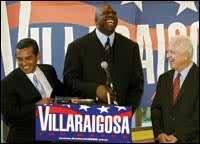

Nicolás Vaca devoted an entire chapter of his book to the 2001 mayoral race in Los Angeles, which pitted James Hahn, son of a well-known white politician who had very strong ties to the black community, against Antonio Villaraigosa, who was a relative newcomer. Hahn boasted endorsements from Earvin “Magic” Johnson, U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) and other important black figures — along with the support of the much more conservative white business community.

Hahn’s black support sunk Villaraigosa. Hahn won with 59% of the overall vote — and a remarkable 80% of the votes from the black community.

It was a different story this year. In his first term, Hahn had fired popular Los Angeles Police Chief Bernard Parks, who is black. Many black leaders felt that Hahn had ignored them, and Johnson, Waters and others who supported Hahn the first time around now threw their support to Villaraigosa. For his part, Villaraigosa worked to build up his ties to black voters. Time after time, he stressed that blacks and Latinos had more to gain by working together than against one another.

It worked. On May 17, Villaraigosa became the first Latino mayor of Los Angeles in a century by a 17-point margin. He did it with half the city’s black votes.

Much divides blacks and Latinos in America. The most recent figures show that median net worth for Hispanic households is $7,932 — almost $2,000 more than the $5,998 median for blacks. But when compared to whites — who, at $88,651, own more than 10 times either amount — the difference pales into insignificance.

The same could be said about many social issues that divide the black and Hispanic communities of the United States. Earl Ofari Hutchinson, a black Pacifica News Service commentator who wrote a radio editorial about the racial conflicts at Los Angeles’ Jefferson High School this spring, may have said it best. “A couple of days after the Jefferson High clash, several hundred black and Latino parents and students held an anti-violence forum at the school,” Hutchinson said. “Speaker after speaker denounced the fighting and pledged to work for peace. The hard truth, though, is that blacks and Latinos are undergoing a painful period of adjustment. They will find the struggle for power and recognition to be long and difficult. The parents and students who pledged to work for peace made an important start.”